The unsung struggle for a life-like voice

A new opera in development at Rensselaer uses acoustic and synthetic voices to highlight challenges for people with non-speaking disabilities

As a Ph.D student at Cambridge University in the late 1990s, I sometimes crossed paths with Stephen Hawking motoring along in his wheelchair. One evening, I found myself seated near him and a female companion in a Thai restaurant. When the waiter approached them, I heard Hawking’s machine-generated voice place an order — word by labored word — for red curry. “AND,” the metallic baritone continued with that detached snarl resulting from the flat speech melody riddled with pauses, “WHITE. RICE.”

I remember being struck by how much effort went into even such a mundane interaction. It made the rest of Hawking’s life — the books, the lectures — seem downright miraculous.

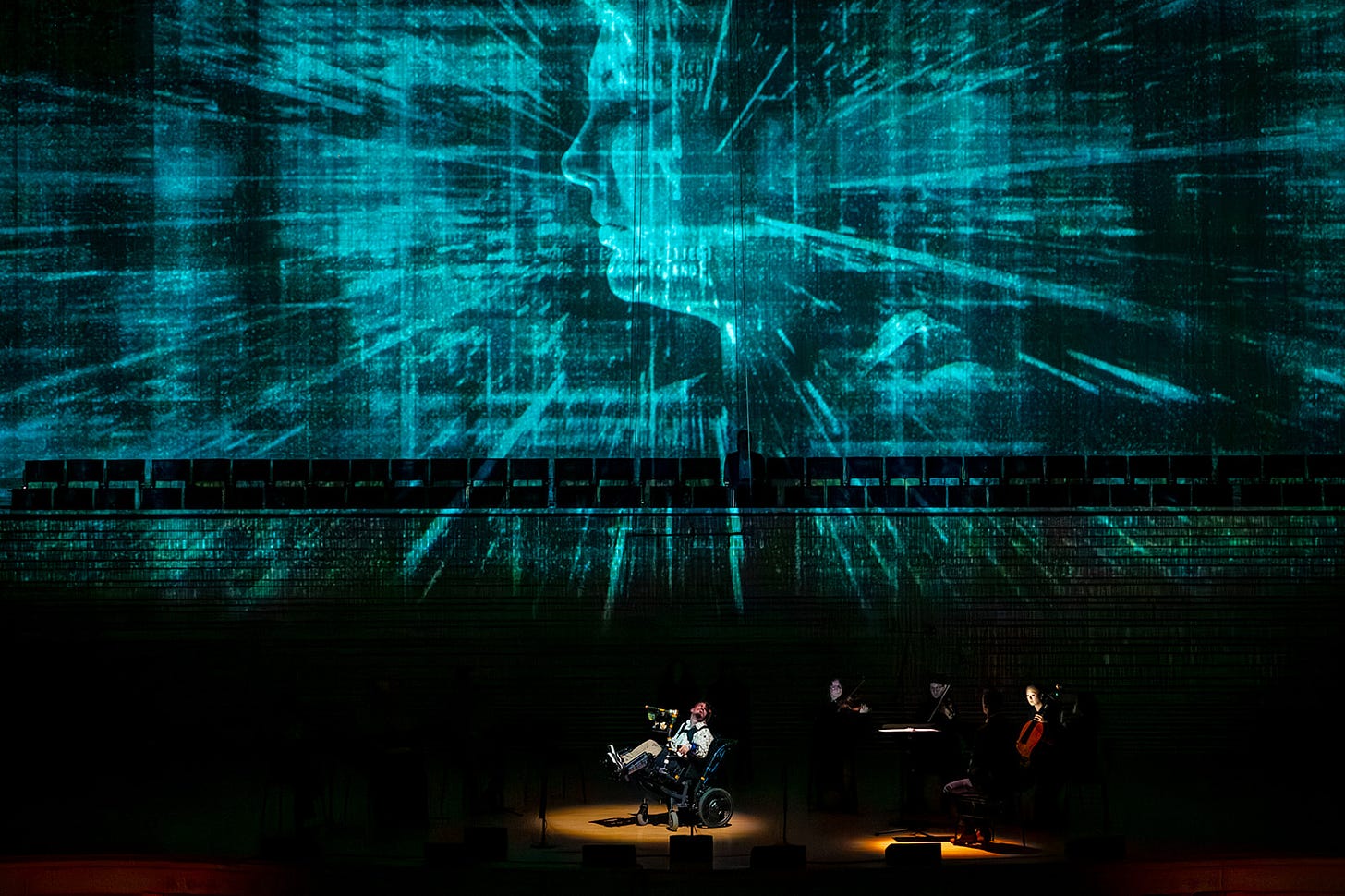

My mind kept turning to that memory as I researched an article for The New York Times about an opera that was workshopped on October 16 at EMPAC, the Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy. Composed by Robert Whalen with a libretto by Mark Steidl and Katherine Skovira, “The Other Side of Silence” features a character who communicates through a text-to-speech synthesizer. The protagonist (based on Steidl) is a non-binary person with disabilities who opts into a pilot program of A.I.-assisted living in the hope of greater agency and freedom. (It doesn’t end well.)

In an email interview I asked Steidl, who has cerebral palsy, how they feel about their speaking voice, which is generated by an augmentative and alternative communication (A.A.C.) device.

“I’m always frustrated because my DynaVox is monotone,” Steidl said. “Because of my sass, I would like to show more emotions. When I say, ‘Darling it’s lovely to see you, may I please have a friendly kiss on each cheek?,’ my DynaVox Maestro isn’t as flamboyantly gay as I am.”

Whalen, the opera’s composer, later told me that there are only six standard voices to choose from for the two million A.A.C. users in the United States. To be clear, that figure includes a wide range of medical conditions including throat cancer and autism, and specific disabilities affect the ease with which people use these devices. But the tones in which they order a coffee, ask someone out on a date or join in a chorus of “Happy Birthday” are largely confined to the same few robotic voices. (Bespoke options exist, but are expensive. Visit the website of Vocal ID to see how you can donate to the human voice bank that makes them possible.)

When Hawking received his computer voice in the 1980s, after an emergency tracheotomy had irreversibly robbed him of speech, there were just three on the market: one based on a recording of an adult man, one of a woman, and one of a young girl. It was that girl’s voice that Mark Steidl first got to speak through as a four-year-old.

Seen against this backdrop, “The Other Side of Silence” appears all the more ambitious and moving. To design the first synthetic opera voice, the work’s creators, in collaboration with researchers from RPI and software developers at Dreamtonics in Tokyo, didn’t just have to teach a voice transformation tool how to sound like a classically trained singer. The software had to learn to want to sound like that. The Dreamtonics algorithm relies on a constant feedback loop from users who rate the naturalness of any given synthetic voice. But to most people who are not familiar with the art form, operatic singing appears anything but natural. Beautiful, maybe; awe-inspiring, for sure. But believable?

In the first act, which was workshopped on Wednesday, it took a while for Steidl’s character to break into song. When they did, the voice commanded attention in part because of its strangeness. The rest of the cast featured operatic voices at the height of the art, including the quicksilver soprano of Jennifer Zetlan and the creamy opulence of Meghan Kasanders’ dramatic soprano. The difference was stark.

And yet the synthetic voice carried an emotional directness that was clearly rooted in the human spirit. This wasn’t some A.I. bot mimicking Maria Callas. The sound, which evoked a timbral blend of boy soprano and countertenor, had a beauty all of its own. This seemed to touch on something of fundamental importance: that the integration of disabled people relies as much on society learning to accept and value their difference as it does on scientific advances to diminish that gap.

One human right that opera is especially well-placed to honor is the prerogative to be unreasonable. Opera can take a feeling and blow it up in slow-motion until the cells in every listener have reorganized themselves around it. The effect relies in part on the excess — on larger-than-life, all-pervading, over-the-top voices. Sure, not all A.A.C. users are “flamboyantly gay” like Steidl. But exuberance of some variety is a universal aspect of the human condition. If the goal is to enable flamboyance in everyone, opera has much to teach.

My article is titled “Can a Synthetic Voice be Taught to Sing Opera?” Most reader comments range from I-hope-not to why-would-anyone-even-want-to-try. In the age of A.I., there’s plenty of well-founded anxiety about machines replacing humans. But that’s clearly not what “The Other Side of Silence” is about. And whatever your tolerance for sonic experiments might be, we should all root for advances in A.A.C technology that help disabled people communicate with something like our own speed, fluency and expressivity — in other words, for synthetic voices to become more musical.